Too often in teacher discussions about student writing we complain, paying too much attention to student writers’ spelling mistakes, punctuation errors, and faulty reasoning. We derisively speak in terms of what’s supposedly broken or ill-informed about their writing and pathologize their triple exclamation points and wild use of emoticons as something in need of fixing or treating. Teachers behave more like doctors, dentists, and nurses when we approach the writing of our students as if it’s diseased, regarding the battery of “diagnostic exams” and “essay clinics” prescribed and administered as a cure for perceived language impairments and seek to eradicate the contagion of slang usage in drill-and-kill writing labs.

Of course what I’m saying is not so different than what’s been said by many, many other composition scholars for over four decades now, which is why I’m so discouraged by the perennial nature of the pedagogical myth that two semesters of English Composition can—or should—completely erase the graphic representation of what a person thinks, feels, and believes. Despite all empirical evidence to the contrary and all the reams and reams of quantitative and qualitative data that’s been researched and published on every variety of longitudinal analysis, large sample experiment, and ethnographic case study, it’s common that composition and rhetoric professors must still endure ideas reflected in videos like this:

Yeah, right… Whatev! ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

This problem is taken a step further by the insertion of the word “sic” after examples of student writing to indicate everything that’s wrong with the supposedly unwashed, uneducated masses—and not in a way that merely implies the specificity of the words belonging to them. Originally meant to designate the “thus” in sic erat scriptum of the Latin phrase “thus was it written,” the insertion of “[sic]” is meant to indicate a verbatim transcription of a person’s wording, but is also used as a means of ridicule, designed to call attention to other people’s errors in writing and derisively draw a distinction between “us” and “them”—in reference to the class of college professors as opposed to the classrooms of students with whom we’re charged with sharing our love of learning. To my mind, the only real writing and composition classroom mistakes that occur have to do with the presumption of teacher superiority and the notions that scholarly betterment is a one-way street, and the knowledgeable transfer of becoming well-versed in the arts of rhetoric and poetic language moves in a single direction.

Nasty Nas said it best 20 years ago; it ain’t hard to tell. Young folks can and do know how to tell their own stories. They prove it every day, in fact, on their devices and with their thumbs. And they’re thinking too. Faculty ought to be meeting students where they are in order to help get where they need to go. It’s the professor’s job to go there with our students and let them show us how they’re writing—more vibrantly and colorfully than ever before.

One of my goals is to see more regional and public HBCU’s like Fayetteville State University, develop greater openness to the possibility that the teaching of writing, at the very least, is the work of all faculty members, regardless of discipline and across every department. Moreover, I’d like to spread the word that the flourishing of rhetorical agency for students is a dialogical process where professors must listen as much as they lecture. As more people begin realizing that African American English (AAE) is a legitimate language, they can better understand that writing with AAE in mind is a particular form of communication that deserves expression and not suppression. Fayetteville State is fortunate to have fluid and unabashed speakers of the African American rhetorical tradition through leaders like our current chancellor. It’s affirming for students to see that they too can make it—and without feeling as though they have to play their Blackness to the left. I’d like to see larger segments of the professoriate from outside the gates of HBCU campuses, beyond the field of composition and rhetoric to rethink the conversation about what’s supposedly so [sic] about Black students’ home discourses being applied as an authentic expression of themselves.

After all, wasn’t Charles Chesnutt among the first to articulate a scholarly theory about vernacular forms of AAE’s literary value and cultural rigor, even as he served as a member of the teaching faculty and head of the university during his tenure at Fayetteville State?

Even the most glowing feedback written by students about English department professors in course climate evaluations are scrutinized more harshly for grammar and spelling (unlike, say for instance, those written about professors in Economics, Chemistry, History, Computer Science, Psychology departments). This despite the fact that students appropriately perceive the rhetorical situation that is the “course eval” as a largely informal, perfectly casual, necessarily ungraded personal expression of their class interactions as a learning experience—and not as an examination. At an HBCU and a century after Charles Chesnutt sought to make similar arguments in his own writings, it is the height of irony that so few HBCU’s recognize the origins and legitimacy of Black English varieties as African Diasporic language expansion, especially since this idea has been embraced by research-based and writing-intensive programs at predominantly white institutions, dating back to the 1970s (at least in theory, if not always in practice).

This is not to say that all students, regardless of race or color, should not also be required to become more proficient writers and speakers of the Language of Wider Communication (LWC), as well as develop some conversational proficiency and literacy in a foreign language. It’s vital that creative professionals be fluent in all conventions and practices of both “standard” and “nonstandard” forms of at least 2 languages. Linguistic diversity is something to be celebrated without one or the other being placed at the bottom of some false pecking order, ranked according to outmoded 19th century taxonomies. If students are frequently encouraged to think and speak and write in their home dialects as an avenue towards LWC mastery, in all classes, across every major, throughout their matriculation, well into their careers, they’d develop more confidence to cultivate their professional voices and become the types of lifelong learners we endeavor to promote. This will help our students seek out audiences of their peers who are meaningfully engaged with the communicative conventions, which they can help shape within their chosen communities. But this can only happen if more HBCU teachers are willing to see misspellings, not always in terms of orthographical errors, but pedagogical opportunities to explore questions of rhetorical agency. Such morphological leaps are meaningful and teachers themselves miss out on the chance to become more savvy interlocutors because of their own dialectal limitations.

The alter/native rhetoricity of AAE is of material significance. The historical and cultural experiences of Black writing matters and it deserves to be understood and valued, not denigrated and eradicated. To slightly paraphrase and contextually reframe John Edgar Wideman’s appraisals of Chesnutt’s considerable cultural contributions, when professors are insensitive to the materials they assess, they misinterpret student writings on the basis of superficial detail and consistently fail to respond to its deeper meanings. We—the teachers of HBCU students— end up failing Black students and institutions in a great many more ways than we realize.

- Student: “WTF are all these red marks on my paper supposed to mean???”

The “happy accidents,” which we too often seek to obliterate through the obsessive correction of errors, only manage to inhibit students’ explorations into phenomenological abstraction. Over-correction places unnecessary prohibitions on students’ abilities to ask new questions and academically traverse uncharted, bleeding-edge territory and begin assuming agency over their written language to produce papers that aren’t [sic], but illmatic.

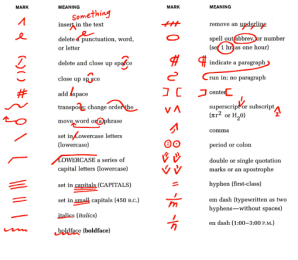

Alas, I suspect, it’s much easier (and less time-consuming) to grade ever-growing stacks of student essays and research reports with fat, red circles, and line-item edits for every other sentence through the insertion of archaic editor’s proofing marks; thus subsuming the writer’s ideas and Black student identity with a cultural eradicationist’s pen, pointed toward displacing unfamiliar viewpoints with concepts and structures that seem less strange to our traditional print literacy standards—at least to our scholarly eyes, lest they be considered in transgression of “proper English” or deemed in violation of the most egregious of all academic writing sins and get marked… awkward.

We miss so much when we refuse student rhetorical agency or try to fix and fit their thoughts into our boring little Blackboard boxes. I believe many fear what ensues when seemingly disparate things are literally con/fused to ignite tiny rhetorical explosions that give rise to linguistic innovation. These are the sparks of intention that bring forth invention. Expression that is both eloquent and meaningful demands the element of amusement and play. Without them writing is petrified, stagnant, and dies (not unlike the Latin we so enjoy inserting into our own, more scholarly publications and used by us more erudite, professors-types ;-) This is why the rhetoricians and compositionists I respect and pattern myself after teach and embrace diversity in written and spoken language.

As for my own part, I’ll do what I can to keep English Composition alive and ill.

![Thus Was It Written: Student Writing That’s Illmatic or [sic]…](https://circuitouslycute.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/1234356_10203826907492341_1578155633_n.jpg?w=960)

Leave a reply to Nicole A. McFarlane Cancel reply